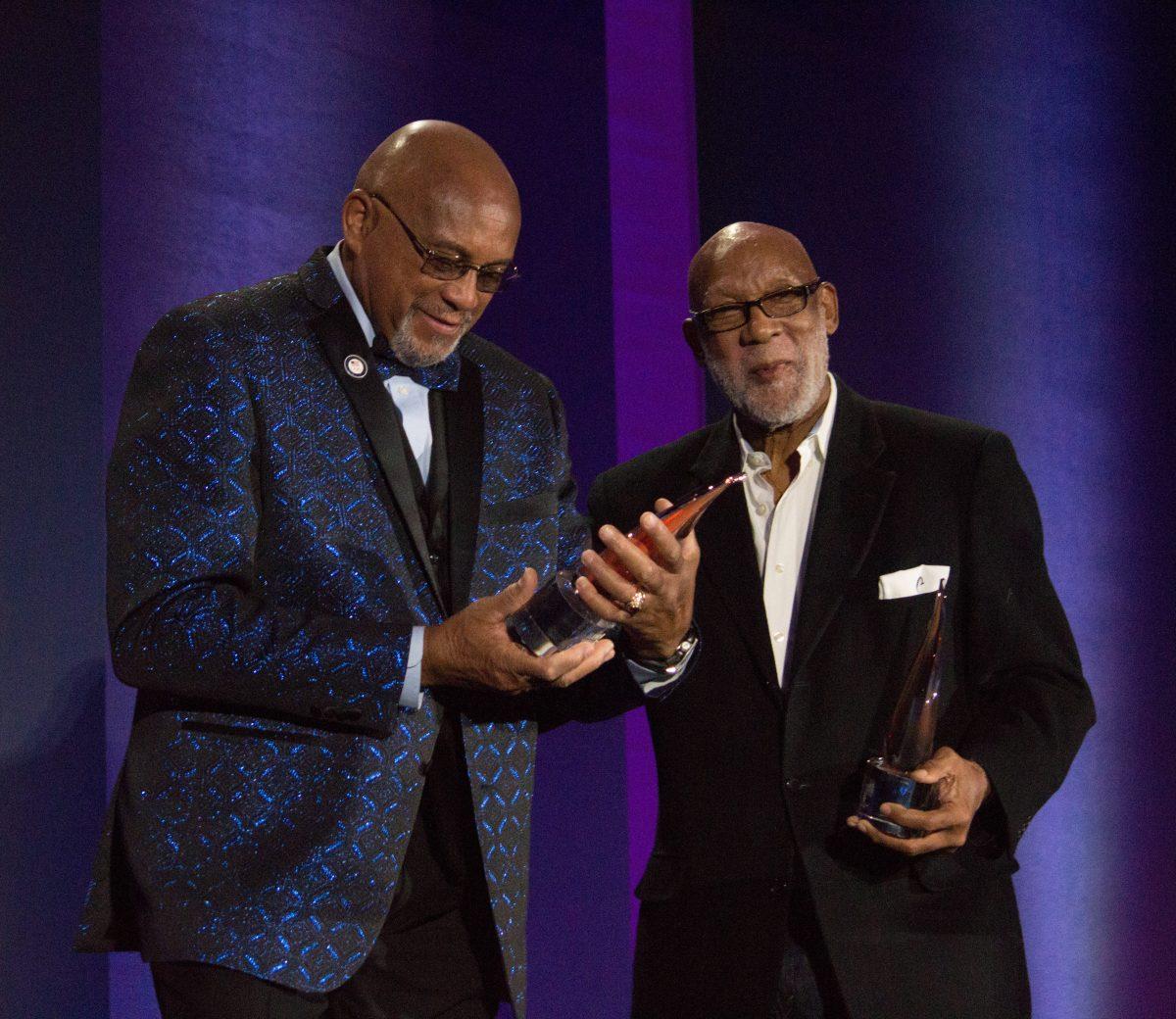

COLORADO SPRINGS, COLO. — Fifty-one years after being expelled from the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City, San Jose State alumni Tommie Smith and John Carlos were inducted into the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame as legends.

“I don’t think Mr. Smith and I can express the love and admiration that we feel, not just those in the audience, but for those that took the time and considered us in their hearts as being a true member of the rings, to have us embedded in the halls of history of the Olympians, the greatest athletes in the world,” Carlos said.

Smith said he accepted the award for the student-athlete who competed in the games, rather than the person he is now.

“I accept this honor for that 24-year-old student-athlete in 1968 for his vision, his Olympic Project for Human Rights stand and of course his spirit,” he said.

The two received their awards Friday during a ceremony at the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Training Center in Colorado Springs after the two walked the red carpet, joined by their wives.

In 1968, Smith and Carlos stood on the medal podium after finishing first and third in the 200-meter race respectively and raised their black-gloved fists while bowing their heads in silent protest of the treatment of Black Americans.

Both took off their shoes to protest the poverty that affected communities predominantly made up of people of color. Smith wore a scarf and Carlos wore beads to protest lynchings of Black men and women in the U.S., according to previous Spartan Daily reporting.

Their protest was not spur of the moment, it was planned through the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Founded by SJSU sociology professor Harry Edwards and then-SJSU student Ken Noel, it aimed to highlight the inequalities and unequal treatment that Black Americans faced.

“We’re not wind-up toys that when it’s time for war, you want to come get us and be in the war for you,” Carlos said. “When it’s time to represent in the Olympics, you come and get us, and outside of that, we’re second-class citizens.”

Their iconic protest got the two expelled from the Olympic village. Avery Brundage, President of the International Olympic Committee, threatened to expel the entire U.S. track team if Smith and Carlos were not suspended by the U.S. team.

Smith expressed similar frustrations as Carlos when he returned to San Jose in 1968 after the Olympics.

“They expelled us from the village and the team, but did they take away the medals from the total count? No. They wanted those medals in the count because of the power and prestige they bring,” Smith said to the Spartan Daily in 1968.

Correcting history

After their protest, Smith and Carlos were shunned and “persecuted” at home. Both men received death threats and were unable to compete in any future Olympics.

Smith described the experience as being “forced into retirement” at age 24.

Carlos called the ensuing relationship with the U.S. Olympic Committee a “dysfunctional marriage,” which required discussion to resolve some issues.

“Even though time has taken its toll, the change is coming,” Smith said Friday. “I’m proud of what I did in 1968 on the track and on the medal stand.”

Carlos used the opportunity as a teaching moment for the audience.

“We learned that the greatest invention was not the airplane, nor the telephone nor your TV, but it’s something everyone in this auditorium [has] used at one point in their lives,” Carlos said. “It’s called the eraser, to realize that we’ve made mistakes in our lives and we can correct these mistakes and move on.”

Student-athlete activism

Both Smith and Carlos encouraged current and future student-athletes to take a stand.

“Keep moving forward proactively,” Smith said. “Don’t sit back for no one, though they say, ‘Wait, you should wait.’ Keep moving forward until waiting gets turned into movement.”

Smith said he viewed his legacy as that of a student-athlete who made sacrifices. He justified student activism by simply explaining that students are human beings too.

For Carlos, he said that young students are the people who will “shape and mold” the world.

“If they have a vision to see something is wrong, and they have the will and the power to bring it to light and roll up their sleeves and say, ‘Let’s get busy and correct the ills of society,’ ” Carlos said.

When asked about student-athlete activism, Carlos said, “It’s necessary, it’s needed, and it’s valued.”

Picking the right platform from which to advocate was a point of emphasis for Smith.

“Find a platform, don’t follow someone else’s platform, because it might not be what you like to see happen,” Smith said. “Find your own platform, move forward proactively, and without a physical battle.”

Smith’s wife Delois added, “And hope it doesn’t take 51 years.”

Joining the Hall of Fame

Smith and Carlos were the first of 12 individuals to be inducted into the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame. The U.S. Olympic Committee had not inducted a new class since 2012.

Susanne Lyons, chair of the U.S. Olympic Committee, thanked Olympian Charles Moore for getting the process started again.

“Last year when I was the acting CEO, [Moore] made an appointment to see me in my office here in Colorado Springs,” Lyons said. “He said, ‘I know you have a couple of other things on your mind these days, but you need to know that it’s been a long time since we’ve done a Hall of Fame induction and you need to get that thing back.’ ”

The 2019 class was selected by a vote that “includes Olympians and Paralympians, members of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic family, and an online vote open to fans.” It was one of the first national sports Hall of Fame classes to use fan voting as part of the process, according to a news release.

Prior to Friday, one Spartan had already been inducted into the Hall of Fame: track runner Lee Evans. A teammate of Smith and Carlos, Evans won two gold medals at the 1968 Olympics as a student-athlete and Olympic Project for Human Rights member. Evans was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1989.

Another inductee

In his speech, Carlos asked for another athlete to be inducted into the Hall of Fame: Australian Peter Norman.

Often forgotten, Norman finished second and stood alongside Smith and Carlos on the medal podium, wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge. Norman too was ostracized after the Olympics, and kicked off the 1972 Australian Olympic team, despite qualifying numerous times, according to previous Spartan Daily reporting.

Carlos said that in 2009, the U.S. Olympic Committee created the Olive Branch Achievement Award for Australian Kevan Gosper and inducted him into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame, despite not being an American.

Gosper won silver in the 4 x 400 meter relay at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia and later served on the International Olympic Committee.

“I feel it would be fitting that we would extend that olive branch to my brother, the late Peter Norman,” Carlos said. “I would hope that we would never ever forget Mr. Norman’s efforts, energy, and vision, and not to mention, courage, standing for what he felt was right in society.”

Mauricio La Plante contributed reporting to this story.