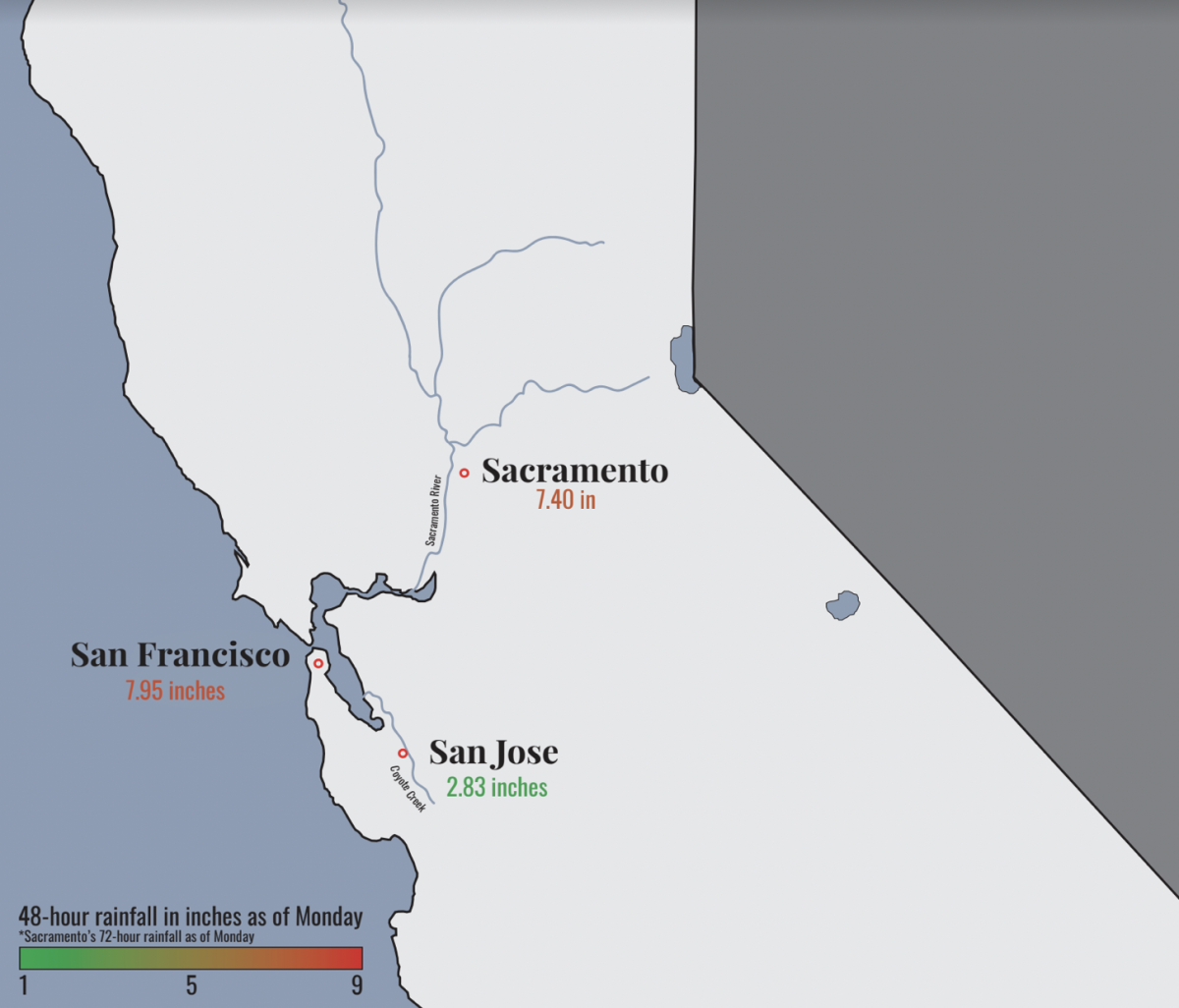

Infographic by Christina Casillas

Heavy record-breaking rains that pummeled the Bay Area throughout the weekend were beneficial for the drought-stricken state but not by much, says a San Jose State meteorology and climate science professor.

Alison Bridger, who holds a doctoral degree in atmospheric science, said the strong “atmospheric river” didn’t substantially contribute to ending the state’s drought.

“We’d have to have several more storms like this to end the drought,” Bridger said in a phone call. “What we really need is water filling up the reservoirs.”

California’s 240 largest reservoirs account for about 60% of the state’s water storage capacity, according to the Public Policy Institute of California website.

The state’s Department of Water Resources compared the amount of water in major reservoirs as of midnight Monday to the capacity of each reservoir and to past levels around the same date.

Monday’s data shows many of California’s largest reservoirs are still holding less water than the historic level for this time of year, even after the weekend’s atmospheric river, according to the Department of Water Resources website.

The two weather events, the atmospheric river and the “bomb cyclone” that occurred in Northern California over the weekend, created the most powerful storm the region has seen in more than a decade, according to a Monday Wall Street Journal article.

Bridger said an atmospheric river is suspended moisture that gets carried in the atmosphere from the tropics.

“Strong rains are what we kind of expect when an atmospheric river comes on shore but then the other component that we need is some kind of storm in the atmosphere to provide the lift to squeeze that moisture out of the atmospheric river,” she said.

Bridger said the “squeeze” was brought by the bomb cyclone, a low-pressure system that pushes moisture.

Sunday’s bomb cyclone was record-breakingly low, contributing to the record-breaking gusty winds and heavy downpour, she said.

Bridger said while some are saying the weekend storm is a sign of an early wet winter, there’s no actual proof of those claims.

California’s climate is characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters that vary depending on geographical region, according to the state Department of Water Resources Current Conditions webpage.

Precipitation is greater in Northern California but the climate can fluctuate from wet to dry years and back again, especially as climate change continues to affect variability, according to the state webpage.

“Nobody has the skill to predict that accurately. Just these days in our science, it just isn’t possible,” Bridger said, regarding claims of an upcoming wet winter. “Just because we had early rain, doesn’t mean it’s going to be a rainy winter. You have to continue to conserve water.”

She said atmospheric rivers, which are common in California, should get more moisture as climate change continues because of the relationship between air temperature and how much moisture the air can hold.

“As the atmosphere warms up and as the air in which the atmospheric river is embedded, the rivers are going to become more juicy in terms of the amount of moisture that they have,” Bridger said. “So we could expect to get more rain out of them.”

She said however, it’s unclear whether the state will see more intense storms as a result of climate change.

“I think anybody who’s been paying any attention to the weather around the world this year will have noticed that there are lots of extreme weather events that have been going on,” Bridger said.

While the weekend’s storm caused disturbances including landslides, power outages and auto accidents, the onslaught of moisture enabled firefighters to fully contain two of the state’s biggest wildfires, according to the Monday Wall Street Journal article.

The 221,835-acre Caldor Fire near Lake Tahoe and the 963,309-acre Dixie Fire near Lassen Volcanic National Park in Northern California are completely contained for the first time since they started in the summer, according to the Wall Street Journal article.

“Given the amount of rain that fell and the really heavy winds, I think the Bay Area came through relatively unscathed,” Bridger said. “But those are all pretty minor things when you compare it to what happened to New Orleans with Hurricane Katrina and what happened to Houston with Hurricane Harvey.”

She said perhaps the biggest point Californians should take away from the weekend storm is that water conservation remains desperately necessary.